The Unravelling

9September 7, 2014 by Paula Reed Nancarrow

Told Saturday, September 6 for Story Arts of Minnesota‘s PROMPT series – “Stories based on, inspired by, or tangentially related to classic works.” In this case, the classic work was The Odyssey by Homer. The theme was “Getting Back.”

By night I pick apart the shroud, thread by thread, for three years, before they figure it out.

“Penelope Unraveling Her Work at Night” – Dora Wheeler (1856–1940). Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

They were young men, not that much older than our son Telemachus, and good-looking, most of them, but not very bright. The shroud was for your father, and for hours each day I walked back and forth in the Great Hall on those platform shoes, wielding the pin-beater through the warp-weighted loom, jamming the weft upwards so that the cloth was as tight as the spot I was in. It would not do to appear careless before the suitors.

I weave a shroud for Laertes since to weave a shroud for you would be to give in to despair; to concede my future lies with one of these boyish brutes. Also you have left me nobody to bury. When the shroud is done, I tell them, I will choose one of them for a husband. They are boys, not that eager to marry a matron, if the truth be known. But they sure like to party.

So I weave into Laertes’ shroud your exploits, exactly the way the bard sung them.

And each night, o man of many ways, old campaigner, I sneak into the Great Hall and pick apart the cloth by torchlight. Torches lit with the warm smoky light of olive oil from your own orchards, not those sulfur-smelling pitchy things you caked in lime to plot the siege of Troy. The patterns dissolve into thread again. They were just stories, after all. Who knows what really happened.

Laertes was off in a cave by then, tending those orchards, where notches in the trees mark your growth from boy to man. Telemachus had notches there too, notches Laertes and I made, notches you have never seen. I can understand his need for work that bears fruit. It gives me hope that he will not fall apart like your mother did. No need for me to travel to the underworld to learn from Anticlea’s phantom lips how she died.

Anticlea in the Underworld, waiting her turn, while Tiresias foretells the future to Odysseus; Henri Fuselli, c. 1800. Courtesy National Museum Wales, National Museum Cardiff, and the BBC.

I can still see her pacing the cliffs in agitation, day after day, one hand shading her eyes, straining in search of a ship, the other clenching and unclenching at her side. I can see each ship disappoint her, as they did me. I stopped going to the cliff’s edge; better to do my pacing at the loom, where some good came of it.

Meanwhile I watched your mother stop her work, refuse food, turn her head to the wall. Cease to speak.

When Laertes, weeping, finally closed her eyes and mouth in death, she had not looked on us with recognition, had not spoken a name but yours, in years. With the other women of the household, I washed her body in sea water, though the custom seemed a betrayal, the sea having swallowed you up. I dressed her hair, the hair she had stopped combing when she stopped speaking – what a task that was! – piled up the white braids, placed the diadem upon them. Affixed pearls to the cold lobes of her ears. I wove her shroud as well. The bard does not mention this. It was pure white linen, white and empty of stories. I hope it gave her rest.

He loved her, you know, that old man. The two had grown old together. He missed their quarrels. Being like-minded isn’t everything. Sometimes I would hear him arguing with himself. His grief was a burden he carried up the rocky hillside each day and let roll over him again each night. All those years he had had to live with the rumor that Sisyphus was your real father. Now he was acting it out.

There were certainly enough stories to bury him in.

Odysseus and Diomedes stealing the horses of Rhesus. Darius Painter, circa 340 BC. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

We can thank the bards for that. I wove in all that I knew then. How you helped Diomedes kill Rhesus of Thrace before he even saw battle, and stole his horses. Horses don’t drink from the Scamander River. Prophecy averted. Troy falls. Clever Odysseus.

How you jumped on your shield instead of on the sandy beach of Troy, because a prophecy had said the first to set food on Trojan soil would be the first to die, so no one would leave the ship. Poor Protesilaus. He missed that little detail. How you won all the funeral games. Did you cheat at those, like you did when you won me for a bride? Deceitful Odysseus.

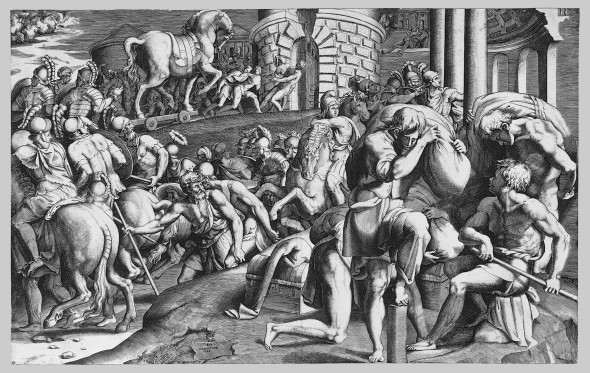

And of course that most famous scheme of your own devising, the Trojan horse. Invading the citadel disguised as something harmless, then attacking from within. Your signature move.

The Trojans Pulling the Wooden Horse into the City. Engraving, Giulio Bonasone, 1545

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum

Clever Odysseus. Deceitful Odysseus. Cruel Odysseus. Why do they need so many adjectives to describe you? Don’t they know your name already means trouble? Isn’t that enough? And the epiphets they used on me! Flawless Penelope. Loyal Penelope. Faithful, constant Penelope. And I am also wise, cautious, clever, cunning. Suitable for you. Like-minded. The bards wanted to make us a match for one another. Though I never hear you described as faithful.

But it’s a base art, storytelling, always trying to pin things down, make judgments, settle once and for all how things were. As if anyone could really know. And don’t get me started on the poetry. Rosy-fingered dawn, the wine dark sea, all those nymphs with lovely braids. Give me a loom over a lyre, any day of the week.

When the suitors discover my plot, they make me finish the shroud.

I told the beggar this. The beggar in his filthy rags who was secretly you. Stories have their uses, do they not? That means they are a craft, not an art – but the bards never want to hear this.

So I finished it. Though in my sleep I still picked apart threads. Not that I slept much at all. The danger was too great. All that weeping I did had as much to do with fatigue and fear as it did with faithfulness. Perhaps you knew this. Perhaps that is why you had to test me. We were no fools, you and I. We tested each other.

Did you think I would not know you, in disguise, you who my harlot cousin Helen recognized so easily at Troy? When Eumaios told me of your beggar self, of how well you knew Odysseus, laying it on so thick that our son must sneeze a warning? – did you think I did not know? When I laughed out loud? And when you would not come up directly, but must wait till evening, I thought I would burst.

Of course the blind bard must bring Athena into all this.

Say Athena put it into my head to show myself to the suitors, and fan their desire, to give you and Telemachus more glory. I will tell you this, Odysseus: I wanted to see you, not show myself. In that I was never like Helen. But the bards are always attributing motives they do not understand to the gods. They think it’s poetic. I just think it’s lazy.

The beggar’s stooped shoulders were broad, like yours. His hands were coarse and gnarled, unlike the hands that had caressed me so long ago. That made me wonder. I looked down at my own hands; they were hardly those of the teenager with babe in arms he’d left. But the giveaway was that barrel chest, plunked atop Odysseus’ short legs. Athena forgot to make it caved and sunken – though perhaps she could not bear to. Even a goddess has womanly feelings – as you are well aware. First Circe, then Calypso – yes, yes I know, you were thinking of me the whole time.

Still, how could I let on, in a house with a hundred men and more ready to kill you, and our son too?

Serving girls in earshot at all times. One of them, surely, the one who betrayed me with Laertes’ shroud. I was not eager to start weaving two more. Even when you volunteer to tend the fires, alone, in the hall, and I come down, we are never really alone. The suitors have dispersed, but servants are still about. We must speak in code.

The Meeting with Penelope. Terracotta plaque, ca. 460-450 BC, artist unknown Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

When you spin a tale of Crete and hardship, I weep for the Odysseus I knew, the one I sent away in fine clothes, clothes you describe precisely as I remember them. Your ocean eyes, those eyes I would know anywhere, stare into mine. They claim Odysseus will return with treasure. But here you are a ruined, solitary man. When your old nurse washes your feet, sees the old scar, and cries out in joy, I turn discretely away, so she does not blow your cover.

We speak of my dream of the eagle and the geese.

You insist it means Odysseus will kill all the suitors, though I cannot see possibly how. It’s going to take more than getting all the armor out of the way. So far that and beating up a real beggar are the only things you’ve managed to do. Perhaps you are not Odysseus after all. Perhaps being Odysseus is not enough.

And then it hits me. How to identify you for certain, and get into yours hands that great bow – the only practical weapon with which one man may hold off many for any length of time. A contest, of course, for my hand.

And this time, no cheating.

The most important mistake in the official version, the poem attributed to that old blind bard, is one I wove in myself.

Penelope Awakened by Eurycleia ), oil on canvas Angelica Kauffman, 18th–19th century. Courtesy Encyclopedia Britannica

I too, can blame things on the gods when I have to. Athena did not cast me into a deep slumber while you slaughtered the suitors. I heard it all, as clearly as I heard Telemachus sneeze. I heard Antinous fall before you told me of it, dropping the two-handled gold cup from his hand, bleeding all over the bread and roasted meats. I heard Eurymachus try to negotiate with you, offer reparations that you refused.

I know what it sounds like, now, for brains to be battered in on a hard packed earthen floor; I hope I never hear it again. I know the sound of a priest’s head rolling on the ground in the midst of his prayer for mercy. Even before you told me of the way Eumaeus and Philoetius hung the goatherd up in the storeroom to die a painful death, I could hear his screams. The women’s quarters are just above the storeroom.

I made your old nurse tell me everything she saw before the hall was scrubbed and purified. I needed to know what you were capable of. But before Euryclea told me how she found you among the corpses bespattered with blood and filth, covered from head to foot with gore, I already knew who you were.

A Pile of Dead Young Men. Detail from The Suitors by Gustave Moreau c. 1851-1852. Musée Gustave-Moreau, Paris.

And I listened to what Euryclea told you. Listened, but could do nothing for the twelve serving women punished as collaborators. Though you might as well have punished the tables and chairs for letting the suitors sit on them, or the pigs for allowing themselves to be butchered and feasted upon. They were women. They were slaves. They were property.

I listened while they carried out the bodies of their lovers, weeping, and stacked them up outside. While they sponged the blood off the tables and chairs, and carted away the gore strewn dirt from the floor.

And when they were done cleaning up, Telemachus – our son Telemachus, who’s never been to war – laced their pretty necks into a ship’s cable, hung them in the courtyard, where they dangled like warp weights, young girls he’d grown up with, playmates.

The blind bard does not tell you that I wept then, but I did.

Now you are off again on another journey.

For that we have to thank Teiresias, who says it’s the only way you can purify yourself from having killed all those suitors. I wish you’d negotiated with Eurymachus. Instead, you have to carry an oar so far inland that the people there mistake it for a winnowing fan. Somehow that is going to appease the vengeful ghosts of the suitors, and their vengeful relatives, and make Poseidon happy.

So I wait again for your return. I keep the home fires burning. And I weave.

Laertes says he wants a new shroud, with all the new stories on it – the ones you told me after that long night of love (thanks for the eclipse, Athena) as we lay in our marriage bed, the one that roots me here, but keeps you roaming and returning. I walk back and forth in the Great Hall on those awful shoes, wielding the pin-beater through the warp-weighted loom, jamming the weft upwards as I recreate the Cyclops, Circe, the Kingdom of the Dead, Sylla and Charybdis, Calypso. I am never satisfied with the results.

My son is impatient for me to get to the final battle, but each night I find myself unable to sleep. Old habits die hard. I go down to the Great Hall, light the torches, begin picking apart the cloth. Often I am at it till the child of morning, rosy-fingered dawn appears – yes, all right, it’s a pretty phrase. It suits that quiet, luminous moment, the moment I find I must be awake for: when anything is still possible, and when no yarn has yet been spun.

![Sailing Ships at Dawn, Konstantinos Volanakis [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://paulareednancarrow.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/volanakis_constantine_sailing_ships_at_dawn.jpg?w=590)

Sailing Ships at Dawn, Konstantinos Volanakis [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Share this:

Related

Category: Stories I've Told | Tags: Odyssey, Penelope, Penelopiad, Story Arts of Minnesota, storytelling

I really enjoyed the way you poke holes into the various retellings of Penelope’s story. Love the last line, too :)

LikeLike

Thanks Lori. That’s especially welcome feedback from a woman on her own odyssey right now…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thoroughly enjoyed your retelling of the story from Penelope’s viewpoint. The wealth of research shows in all the many details you give – before, during and after Odysseus’ return. For me, you brought Penelope’s voice alive.

LikeLike

Thanks, Teagan. I enjoyed the work that brought the story to pass.

LikeLike

What deity shall I thank for leading me to your wonderful heroic Penelope? At least let me thank you for sharing this!

LikeLike

Thank you Joe, that was very kind. Thank any and all deities you wish!

LikeLike

[…] I did one such event last year when the classic work was The Odyssey, which I retold from the perspective of Penelope. (Yes, I referenced Margaret Atwood.) You can read the end result here. […]

LikeLike

Very nicely done, you have a fluid and easy storytelling voice.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike