C’est le Premier Pas Qui Coûte: Mary McCarthy and Me

10February 2, 2015 by Paula Reed Nancarrow

I was looking for a small ugly box of a house. But of course it wasn’t there.

If you go to 2427 Blaisdell Ave. S. in Minneapolis today, you will not find it either. Instead of the home where Mary McCarthy, author, critic and political activist, lived from 1918 to 1923, you’ll find a large ugly 1950s apartment complex. The Whittier neighborhood, known for its diversity now, is no longer organized around the parish of St. Stephen’s Catholic Church.

Times have changed.

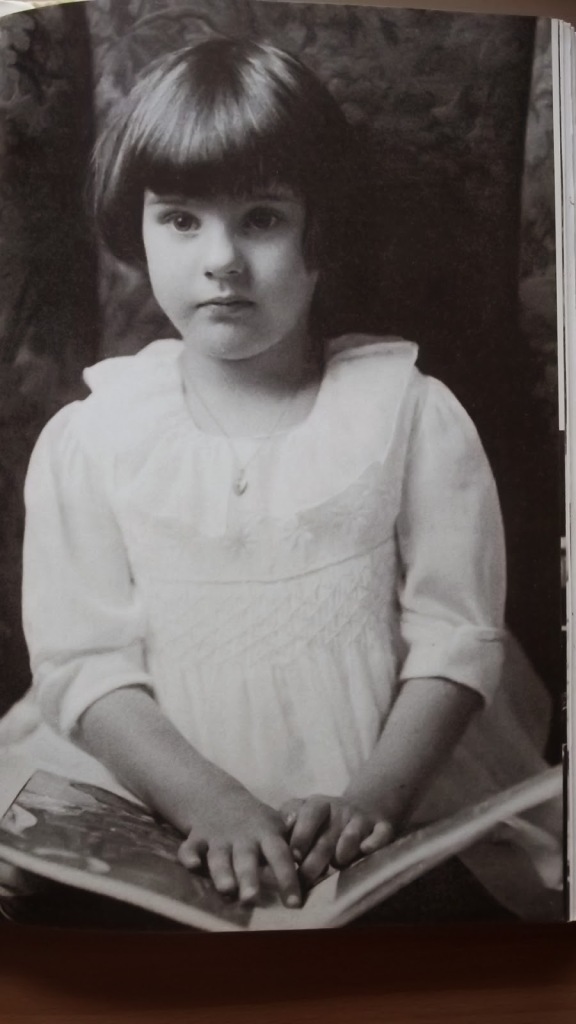

When you get your flu shot, it will be to keep from getting sick and having to miss work – who wants to use Paid Time Off for that? It will not be to keep your children from becoming orphans. But at the height of the flu pandemic of 1918, that’s what happened to Mary McCarthy and her three brothers. The family was moving from Seattle, her mother’s home, to Minneapolis, where her father’s family was. Mary was six. Her father’s brother had come out to fetch them.

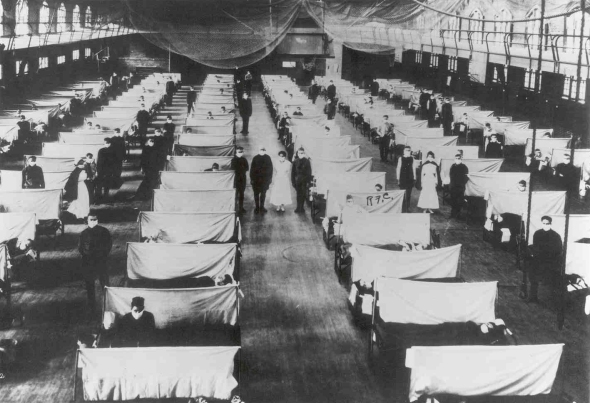

Influenza was traveling from east to west at the time, and Minnesota had been hard hit.

Courtesy of the Office of Public Health Service Historian

In October, 75,000 were struck with the disease; 7500 died in that month alone. Her uncle and aunt may have unwittingly brought the disease out with them. Her father, never strong, was possibly sick when they got on the train. One by one, the rest of the family followed. Both parents died within days of arrival. The children eventually recovered.

The story of those years in Minneapolis, the orphaned children consigned to live with a cruel great-uncle and aunt, reads like a Grimm’s fairy tale, but McCarthy is in fact a scrupulous historian. She writes the story as she remembers it, given some plausible reconstruction of conversations, then distills the art, cross checks her memories with those of others, notes disparities, and draws what conclusions she can about her own past, and how it has shaped who she became.

Memories of a Catholic Girlhood is a book I read over thirty years ago.

I remember little about the Dickensian fate of the orphans, really, though that part impressed me at that time. What haunts me instead is another chapter in McCarthy’s memoir, which takes place after Mary and her siblings have been rescued from the clutches of Great Aunt Margaret and Uncle Myers by the Seattle grandparents, and Mary is attending Sacred Heart Convent School.

At her new school, she is not popular. This bothers her. She begins a campaign to convince the older girls of her worth. “It was the idea of being noticed that consumed all my attention; the rest, it seemed to me, would come of itself.” Things do not particularly go well. Eventually she determines she will get herself recognized “at any price.”

That’s when she hits on the plan to lose her faith.

I had decided to do it before I knew what it was, when it was merely an interweaving of words, lose-your-faith, like the ladder made of sheets on which the daring girl had descended into the arms of her Romeo. “Say you’ve lost your faith,” the devil prompted, assuring me there would be no risk if I chose my moment carefully. Starting Monday morning, we were going to have a retreat, to be preached by a stirring Jesuit. If I lost my faith on, say, Sunday, I could regain it during the three days of retreat, in time for Wednesday confession. Then there would be only four days in which my soul would be I danger if I should happen to die suddenly.

And so it begins. “I was always an ostentatious communicant,” she says. But this Sunday she remains sorrowfully in her pew. At lunch she maintains a mournful silence as she rehearses what she will say to Madame MacIllvra. Nuns in the Convent of the Sacred Heart were not referred to as Sister Margaret or Sister Mary Clare; they did not lose their surnames, but were referred to as Madame or Ma Mere, as if they were French nobility who had fallen on hard times: which, when the order was founded in the wake of the French Revolution, they were.

Alarmed, but not surprised – “evidently my high standing in my studies had prepared her for this catastrophe” – Madame MacIllvra calls the Jesuit chaplain, Father Dennis, from the neighboring college. She instructs her to go to her room and not speak with anyone. When Father Dennis comes, she will be sent for.

Madame MacIllvra’s alarm is contagious, and alone in her room, Mary realizes the flaw in her plan.

“I knew nothing whatever of atheism.” In a Catholic boarding school, books on the subject were simply unavailable. She was going to be found out. She had been taught something about skepticism, the produce of “false science.” As she begins to think the problem out, desperate not to get caught in her deception, “doubts that I had hurried stowed away, like contraband in a bureau drawer, came back to me, reassuringly. “ Alone in her room, she concocts an elaborate argument against the Resurrection of the Body involving cannibals. Others followed. “Elation had replaced fear. I could hardly wait now to meet Father Dennis and confront him with these doubts, so remarkable in one of my years.”

Then something else happens that Mary had not anticipated. The responses the Jesuit gives prove less convincing than her own questions.

He dismisses her argument about cannibals with a wave of his hand. “These are scholastic questions…beyond the reach of your years. Believe me, the church has an answer for them.” But he refused to tell her what it is. Arguments about the divinity of Our Lord do not fare much better. ”

“You must have faith, my child,” he said abruptly.

The awesome thought struck me that perhaps I had lost my faith. Could it have slipped away without my knowing it? “Help me, Father,” I implored meekly, aware that this was the right thing to say but meaning it nevertheless.

I seem to have divided into two people, one slyly watching as the priest sank back into the armchair, the other anxious and aghast at the turn the interview was taking.

In the end, instead of pretending to lose her faith, Mary finds herself pretending, for the sake of those around her – who have, finally, noticed her, and are distressed on her behalf – to regain it.

“C’est le Premier Pas Qui Coûte.”

That’s the title of the chapter in McCarthy’s book. Loosely translated, it’s the first step that costs you. The story stuck with me because in spite of the many, many differences in our lives, I recognized myself in in it. What I recognized when I read the book in 1979 or 1980 was a piece of my past. What I did not recognize at the time – and what I hope to explore a little further on February 10 when I do Two Chairs Telling at the Bryant Lake Bowl with Brian “Fox” Ellis – was the piece of my future the piece held as well.

Reblogged this on Once A Little Girl and commented:

I found this story because I follow Paula on Twitter (@prnancarrow)

My “Once A Little Girl” loves the picture painted by the words of the Little Girl Mary McCathy. I hope you like it as much as I do.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for sharing, Adela. i appreciate it!

LikeLike

I taught elementary school for 6 years–1st, 2nd, & 4th grades. I have to love a child this audacious! Kids continually inspire me.

LikeLike

We do now, don’t we? I think that’s part of the sadness of this story… and part of the triumph too.

LikeLike

I think it’s still sort of a crap shoot. Some people become teachers because they love kids. Some because they love learning. Everyone’s different.

LikeLike

There is so much in this post I can connect too. Being catholic and understanding the pressure to believe. My mother went to a Sacred Heart school in Chicago were you spoke french. Most powerfully, I can remember my Dad talking about the year of the flu. Both his sister and mother were very, very sick. That year he did not attend school because all of the public schools in San Francisco closed. Years latter when both his mother and sister died 3 months apart; he blamed the flu for a weak immune system. Wonderful post!

LikeLike

I am so sorry not to have gotten back earlier to acknowledge your comment. It was a hectic work week. McCarthy says those Sacred Heart schools were nearly identical; “the same blue serge dresses, usually, with white collars and cuffs, the same blue and green and pink moire ribbons awarded for good conduct, the same books given as prizes on Prize Day, the same recitation of ‘Lepanto’ by an English actor in a piped vest, the same congés, or holidays, announced by the Mère Supérieure, the same game of cache-cache, or hide-and-seek, played on these traditional feast days…” and it goes on. It is hard for us to remember with all the silly Nyquil & Dayquil commercials how truly devastating a pandemic flu can be.

I looked at your very interesting blog, mainly because I wanted to be able to refer to you in my comment by name, and not just as Metaphysical Quilter (which seems a little impersonal) but was not able to find one. Is that intentional? It’s rather odd to see such a lovely resume and not know whose it is! At any rate, my thanks for the compliment.

LikeLike

Thank you for reminding me of that wonderful book.

Have just retrieved it from a packing box after a house move.

LikeLike

That’s lovely to know June – thank you!

LikeLike

[…] I said last week that I recognized myself in Mary McCarthy’s story. This is part of the reason why. […]

LikeLike