Lost in Transfiguration

11February 14, 2016 by Paula Reed Nancarrow

I went to church last week.

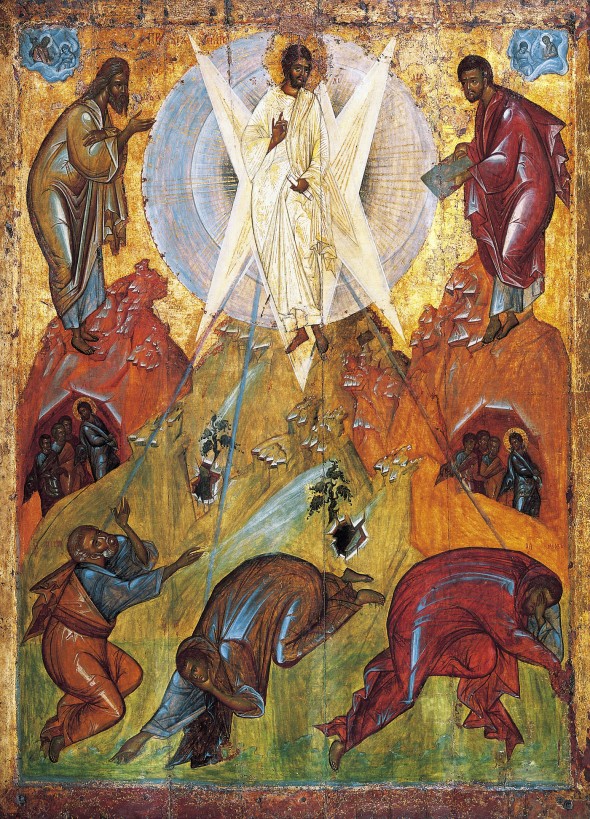

I call myself a Buddhist by practice and a Christian by culture, but I don’t practice much. I’m not a practicing Christian either, but I can usually speak the language. It was Transfiguration Sunday, and my daughter the Youth Minister was preaching the sermon. The one for adults, no less.

Before the adult sermon, the children come up for a talk of their own. A children’s sermon. There is a separate Children’s Minister for that. This is a church that believes in, and supports, ministry to families.

The Children’s Minister asked if anyone knew what Transfiguration was.

A bright- eyed girl raised her hand and promptly announced, “A class in Harry Potter!” There was some embarrassed laughter. The child who had spoken up was – of course – the eldest daughter of the Children’s Minister. As a clergyman’s wife for seventeen years, I have the right to my “of course.”

“Well, yes,” the Children’s Minister – aka Mommy – admitted. “But we’re talking about the Transfiguration of Jesus now. Did Jesus turn himself into an owl or a snake or a newt?” “Nooooo!” giggled the children – the loudest “no” coming from the youngest daughter of the Children’s Minister. Little bit of sibling rivalry going on there.

It wasn’t exactly an Art Linkletter moment, but it was close.

My daughter’s sermon was more about Peter than it was about Jesus – about his imperfect nature.

Peter had a yearning for something more. For a higher purpose. And now here he was, on top of a mountain with his teacher and a few other disciples. And Moses. And Elijah. He wanted to keep it that way.

“Let us build three booths,” he said. To keep Moses and Elijah around, keep that radiance in Jesus’ face, keep the authorities and the Messianic evidence readily accessible and protected. Peter, the Rock on which the church would be built, was eager to get started. But there were other things that had to happen first. Things Peter would have no control over, and – at least now – little capacity even to imagine.

Peter was not what we’d call “content.” Though he is described as such in a hymn I hold dear.

They cast their nets in Galilee

just off the hills of brown;

such happy, simple fisherfolk,

before the Lord came down.Contented, peaceful fishermen,

before they ever knew

the peace of God that filled their hearts

brimful, and broke them too.

There’s that problematic word “peace” again – the one we discussed last week. In the first line it is fits neatly into the dictionary definition – “freedom from disturbance; quiet and tranquility.” In the third and fourth lines, it is a paradox of Biblical proportions.

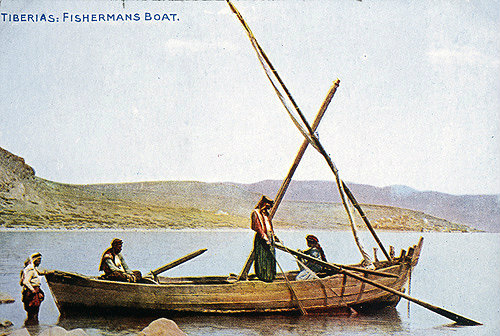

Fisherman’s Boat, on the Sea of Galilee. Postcard circa 1920. Not much different from the boats used by Peter, Andrew and John.

Young John who trimmed the flapping sail,

homeless in Patmos died,

Peter, who hauled the teeming net,

head-down was crucified.The peace of God, it is no peace,

but strife closed in the sod,

Yet let us pray for but one thing —

the marvelous peace of God.

The hymn is American-made, not an Anglican import. It is in the 1982 Hymnal, which some Episcopalians probably still call the “New Hymnal,” though it came out the year I was married. My children were born in 1987 and 1989, respectively. I was divorced in 2004. So the newness of that hymnal is now very far away.

They Cast Their Nets is one of those hymns I cannot sing.

It chokes me up. I’m not a practicing Christian, and yet the music and the poetry still move me on a level that is independent of dogma or creed. I am not sure what that is about. It is like a door to the past opens, and I drop down into it.

What am I crying for? For these men, who had the courage of their convictions? For my lost faith? My trust in the enduring nature of love, in my ability to keep my own promises? For a simpler time? I do not know.

Fortunately my daughter is serving at the moment in a Methodist church. They have their own hymns, which do not make me cry.

A con tented man did not write this hymn.

tented man did not write this hymn.

They Cast Their Nets is a poem by William Alexander Percy. The scion of a aristocratic Mississippi family with a 20,000 acre cotton plantation on the Delta, Percy does not at first seem a likely candidate for romanticizing simple fisher folk. But Percy was also the author of Lanterns on the Levee, a 1941 memoir that defended, while it mourned, the Southern Way of Life.

As a young man, Will Percy attended Sewanee: The University of the South, on Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau. This was back when it was a small men’s college of three hundred.

His description of the place, from Lanterns, is still on the university’s web site:

It’s a long way away, even from Chattanooga, in the middle of woods, on top of a bastion of mountains crenellated with blue coves. It is so beautiful that people who have once been there always, one way or another, come back. For such as can detect apple green in an evening sky, it is Arcadia—not the one that never used to be, but the one that many people always live in; only this one can be shared.

Percy was not a simple fisherman, but he was, like Peter, imperfect.

He had a year abroad in Paris, went to Harvard for a law degree he was not especially eager to earn. Then he dutifully joined his father’s practice. He did not dutifully marry and have children – though there was considerable pressure on him to do so, his brother and only other sibling having been killed in a hunting accident. His failure to do so distressed his Roman Catholic mother. His father, a nominal Episcopalian in whose powerful shadow he led much of his adult life, thought him “queer.”

Then came the Great War. He became a captain in the army, and won the Croix de Guerre. At least no one could call him a sissy now. Again he came home, took up the law, lived in his parents’ house. Wrote four volumes of poetry. From 1925 to 1932 he edited the Yale Younger Poets series. In 1934 he would publish a poem as A. W. Percy – a pseudonym that barely disguised him – in an anthology lauding classical homoeroticism, Men and Boys.

They Cast Their Nets was published in 1924, by a man who knew of war, and conflict, both internal and external.

An elitist with a sense of noblesse oblige and a distrust of the “white trash” Ku Klux Klan he and his father drove out of Greenville; a man who courageously led the Belgian Relief Effort before America even entered the Great War, only to come home and have his efforts to evacuate black sharecroppers in the Great Flood of 1927 undermined by his father and the rest of Greenville’s planters, who feared once their cheap source of labor left, they would not return.

A man who, though he travelled broadly, lived his entire life as a “confirmed bachelor” in his parents’ home. Who adopted his cousin’s three boys after their father’s suicide, and raised them as his own. One of these was the novelist Walker Percy, whose literary accomplishments, as well as his understanding of race relations, far eclipsed his uncle’s – though he maintained a deep respect for the man, as can be seen in the introduction to Lanterns on the Levee he wrote in 1975.

Walker Percy vigorously maintained that there was no evidence his adoptive father was a practicing homosexual. Another cousin, gay activist and pedaresty rights advocate William Anthony Percy III, maintains just as vigorously that there was plenty, insisting “Will had in succession three teenage African-American boyfriends in Greenville, each a servant of his.” It is the abuse of power, not the closeted identity, that makes me weep, if this is so. No amount of romanticism and nostalgia can make this smell like liberation, or as one recent biography puts it, “freethinking.”

Though this hymn has long moved me, until now I did not know I had a personal connection to its author.

We lived in the rectory at Sewanee for a year while my husband was Interim Rector at Otey Memorial Parish. He was almost done with his coursework at Vanderbilt and beginning his dissertation. He hoped to teach in an Episcopal seminary. There were only a dozen or so in the country.

Now here we were, magically deposited for a year on the top of a mountain. With an Episcopal seminary. There was some wistful booth-building going on in the rectory around this prospect. Though I wasn’t entirely along for the ride.

It was, in many ways, Arcadia.

Aidan and Maggie, in second and fourth grade at the time, played in the woods, rode their bikes all over town, knew all the neighborhood kids. Heck, the town was the neighborhood. But it was an isolated, insular, town and gown community, with very little diversity. It was expected that faculty send their high school children to St. Andrew’s, a private Episcopal school on the mountain – there was nothing else considered “suitable” at lower altitudes.

I did not think the environment would always be good for them. Or for me. My options seemed dependent on where God called my husband. That hadn’t seemed to phase me before; I thought I could be happy and fulfilled anywhere he was happy and fulfilled. That was what love was all about, wasn’t it?

There was a sort of local mythology at Sewanee – it persists today – that the school was close enough to heaven to have its own guardian angels.

When you passed out of the stone gates of the university, you were supposed to touch your hand to the interior roof of the car, to take your personal angel with you; when you returned, the same gesture would (supposedly) release it. On the mountain, apparently, you didn’t need an angel. You were safe.

I did not see Jesus transfigured on The Mountain.

Though with my children and their father, I stood on the roof of the Cordell-Lorenz Observatory and watched Halle Bopp cross the sky, squinting into the lens, then passing it, relieved, to the next in line. It was a rare moment, but almost anticlimactic. After all, here, without the telescope, were all the stars you could ever want to see, splattered across the sky. Insular? How could a place with such an expanse of stars be insular?

And yet.

Eventually we too, had to come down from the mountain.

No seminary job materialized. We returned to Nashville, where another interim position opened. And the conflict was deferred. But something was begun in me. Was it a worthy yearning? Or mere discontent?

As I sit here writing this I have my Sewanee angel afghan over my knees. It’s old. It’s coffee stained. It has a hole in it. But it’s still my favorite throw.

Just like that hymn still chokes me up.

So much of this post resonates with me. I love the way you meld a whole lot of different things together — faith/family/music/art/humour/loss/history….

I had never heard that song, so did a youtube search (successfully, I am happy to report). The peace of God that passeth all understanding is truly something other than what we normally consider peace to be. Yet the promise “And the peace of God, which passeth all understanding, shall keep your hearts and minds through Christ Jesus.” (Phil 4:7) is still one that I cling to. Peace, in the midst of turmoil, and tragedy, and the sometimes horrific situations we are faced with: Hope.

That throw is lovely! From my perspective there appears to be a whole lot of humour woven into it.

LikeLike

Yes, it is a whimsical throw. I think that is what keeps it together when a cat starts pulling on the fringe. ;-)

None of the recordings I found actually carried the power of being immersed in this sound in the midst of a congregation for me, but the one that came closest was this one: .

Oddly enough, I can sing it accapella in the car and still get choked up.

LikeLike

As I was reading this and your deeply emotional response to hearing the hymn, it took me down my own memory lane. There have been a few instances in my life where I have had a deeply emotional response triggered by seeing someone from my past unexpectedly. I have come to understand those as moments of Grace when I have had a cathartic cleansing that is so deep I wasn’t even aware I needed it.

LikeLike

Yes. Thank you. I think you are right in that regard.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This felt like a marvellous tapestry of thoughts and emotions that swept me away in so many directions that it made me emotional just reading it, It resonates with emotional impact, and I loved the trip.

LikeLike

Thank you, Judy/Judith/Judi. ;-) I’m a little uncertain about the number of directions this story goes in, and it probably needs to be explored in a longer piece, but sometimes you just have to describe what you can and wait for the rest to arrive. I actually added a paragraph later in the week that was not previously there, which is something I rarely do.

LikeLike

The name thing’s weird, isn’t it? But I write romances under a pen name–ugh. Your story did have a lot of different directions this time, but it didn’t feel fractured. For me, it all came together into a whole, and I really liked it.

LikeLike

The peace of God, it is no peace,

but strife closed in the sod,

Yet let us pray for but one thing —

the marvelous peace of God.

Upsetting lines, as though belief in the peace of God as marvelous is essential even though the peace of God is no peace at all. Maybe I’m missing something. I’m with you as you move from Buddhism to the Christian mountain top to Halle Bopp. A woman on a quest with little contentment in sight, except maybe that old throw over your knees as the search takes you where it will.

My sons don’t take me to church. I took them to an eclectic Sunday School where they learned a little about meditation, Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and whatever other traditions we parents could share with them.

My most meaningful encounter with Christianity was at a church camp when I was around 12. A mystical experience at sunset, sitting on bleachers, watching pink clouds, singing “Now the Day is Over” with the other kids. The high lasted for days, but it took many years to realize that under all the philosophy and questing, I’m a nature mystic.

(In the last line of your first poetry quote, there’s a repeated word, “them them.” I tell you because I’m glad when people point out these things to me.

LikeLike

They ARE upsetting lines. I think the shift is from peace as tranquility and safety to peace as confidence in the face of suffering – whether it is the suffering caused by war, or martyrdom, or having to fragment your identity. Although I have no idea what the author thought God thought of his sexual orientation. I’ve not had the chance to study his life in detail. At any rate, I think that is what moves me. I too, am a nature mystic. Which is not incompatible with Christianity, unless you confuse it with paganism, which some fundamentalists do.

And thank you for finding the them them. One of them has been removed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reading this helped me to see beneath the surface of your online persona and learn a bit of who you really are. I wish it had been longer. It’s interesting how music can touch us to the core and bring back so many of our associated memories.

LikeLike

Thank you, Barbara. It probably should be longer. I actually did add a paragraph, but it is still far from complete, I think because my understanding of the experience is still evolving. Some stories should perhaps remain fluid.

LikeLike