The Making of a Liar

9December 11, 2016 by Paula Reed Nancarrow

I am on the phone with my parents, who live one thousand and sixty-seven miles away in upstate New York.

I am twenty-two. I am living with two other women in a peach colored stucco triplex on the corner of 32nd and Emerson. We didn’t have stucco in New York, or if we did, I’d never noticed it. In Minneapolis, stucco is everywhere, liked canned icing on a Betty Crocker cake. But peach: that stands out.

I have just finished my first year of graduate school in English at the University of Minnesota. I’ve become a vegetarian. I am deconstructing James Joyce. I pay rent.

My parents had planned on coming out to see me that summer, but are telling me on the phone now that they’ve have changed their minds.

They have changed their minds because during spring break I had gone to visit my old college boyfriend David, who was a VISTA worker in South Carolina, where he was educating textile workers about brown lung. Yes, that was a thing.

They have changed their minds because I had stayed in his apartment. My parents did not approve of this visit, so they had to take a stand.

My mother doesn’t really take stands. My father takes stands, and my mother agrees with them. That is how you get along with my father. Especially now that he is retired. You can take the principal out of the school, my brother says, but you can’t take the school out of the principal. All that concentrated authority has to go somewhere.

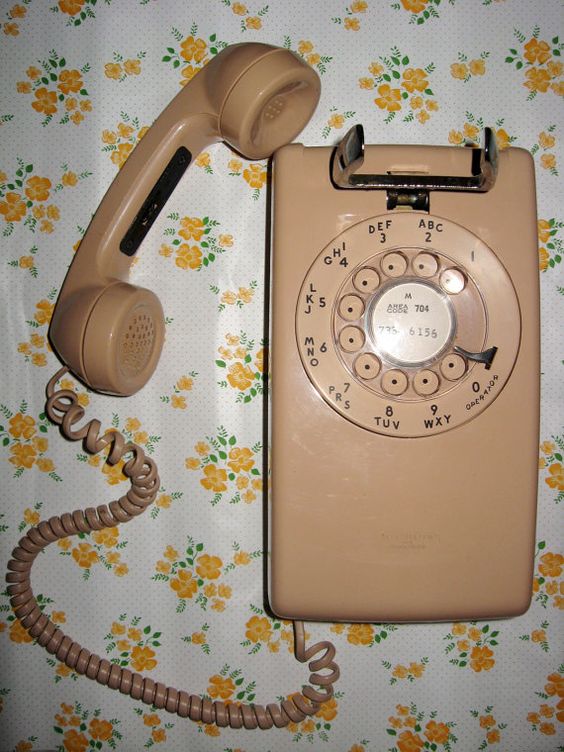

You are perfectly right. I HAVE used this picture (courtesy ecastro/Flicker) before.

My mother is silent while my father explains their position.

I can tell she is on the upstairs phone because of the extra static. My ear is to the receiver, but I’m not really listening. Instead I’m hearing my father’s old two-part refrain, familiar from all our battles during my adolescence – over religion, over politics, over sex.

When you are twenty-one, you can do what you like. But as long as you’re living in my house and I’m paying the bills, you will do what I say. I am your father.

Twenty-one was the magic age because it was when my father had legally been allowed to vote, and to drink, in Pennsylvania. Both of those privileges had been granted to me in New York at the age of 18 because boys in Vietnam had died before they could do either.

I speak into the receiver.

“You told me that when I was twenty-one I could make my own decisions.”

“A father has to use his influence,” he insists.

“You’re not responsible for me anymore, remember?”

“I am still your father,” I hear him say. “I will always be your father.”

Then I’m startled by my mother’s disembodied voice.

“Why do you even tell us these things?” she asks. The line crackles. “When it’s something you know we don’t approve of, why don’t you just keep it to yourself?”

Before I can even answer, my father interrupts. “Oh no,” he says.

And there is a rhythm to his punctuated words. I can practically see his middle finger stamping them into the air as he stands by the kitchen phone. “Don’t encourage her to be a liar. I want to know everything. I’m her father. She shouldn’t hide anything from me. ”

Courtesy Viral Novelty.

“Don’t come then,” I say.

Later that day, I call David. We haven’t talked since that my visit. Which in truth had not gone that well. He was an old boyfriend for a reason.

“I have some free time this summer,” I say. “Do you want to come up? Bet you’ve never seen peach stucco.” We make arrangements. I do not tell my parents. When the visit ends in our breakup – as I pretty much knew it would – I do not tell them that either.

Told at the November 2016 StorySlamMN!, for the theme “Lies.”

Share this:

Related

Category: Memoir, Stories I've Told | Tags: family life, lies, memoir, parenting, relationships

I really appreciated this piece — it brought back a lot of memories of that time in my life. Loved the photo of the phone.

LikeLike

Thanks, Jan. Yes, that was back when dialing a number actually meant something…

LikeLike

This was such a good post. I’m dying to know what happened next!

LikeLike

Ahh. What came next is that I came to consider lying something I needed to do to protect my privacy, and I became angry and resentful. I am sorry I kept you waiting so long for such a short answer! It was a busy December, and is shaping up to be a busy January as well.

LikeLike

Great story! Oh, the tales we didn’t tell–and the ones we did. My widowed mom was tolerant (or was it disinterest?) and didn’t freak out when I got drunk in high school or when she realized I was having sex with my boyfriend, the one who had a black eye when he picked me up on our first date. She didn’t need to know about hitchhiking in Mexico and other adventures that felt on the edge even in the 1960s. She didn’t ask. I didn’t tell.

My dad died when I was 14. I had an idealized girlish view of him, but he was already laying down too many rules about lipstick and high heels. I think he would have been a lot like your dad.

LikeLike

Thanks, Elaine. It seems I went into hiding over the holidays without even realizing it. Online overload, I guess. Your assessment of your own parents is wry and honest. Tolerant or disinterested, indeed. Lipstick, high heels, and 14 year old girls. Now that was the sixties. What I remember being my big 60’s controversy was whether my mother would allow me to wear jeans to school after the school decided to allow girls that privilege. I think my mother’s attitude was it may be allowed, but it’s not nice.

LikeLike

Loved this piece. Made me think of both sides of parenting–being the kid and being the parent. Neither are so easy:) And it’s hard to change roles. But boy am I happy my dad wasn’t a principal!

LikeLike

What was he, Judy?

LikeLike

He was a tool and die setter, and pretty easy going, but there weren’t a lot of gray areas in how he saw life, pretty black and white, but fair. Hope your holidays were as good as possible.

LikeLiked by 1 person